Any sign or form produced by the federal government.

No

Languages in Canada

Canada is an officially bilingual country, with two official languages: French and English. In practice, however, the majority of Canadians speak English, with progressively smaller numbers speaking English and French, English and some other language, or only French. The complex power relationships between these four groups forms one of Canada’s longest-running political dramas.

English speakers vs. French speakers

As discussed in the people chapter, the majority of Canadians trace their ancestry to somewhere in the British Isles, and 17.2 million Canadians, or about 50 per cent of the population, claim English as their first and only language. If we include Canadians who speak English as a second language (mostly immigrants and French-Canadians) or native English-speakers who learned a second language at some point, the rate of English fluency in Canada climbs to around 90 per cent.

French speaking Canadians, known as French-Canadians or Francophones, are a much smaller percentage of the population, and more than 90 per cent of them live in Quebec — the only province where French is the language of daily life. 3.8 million Quebecers can only speak French, while another 3.2 million can speak French and English. Together those groups comprise basically the entire provincial population. Small but significant French-speaking minorities also reside in the provinces of New Brunswick (29 per cent), Ontario (2.4 per cent), and Manitoba (1.6 per cent). Everywhere else, native French speakers are exceedingly rare.

Canadian English

Canadian English is mostly a mix of American-style pronunciations and a complex mix of British and American spelling, with a few uniquely Canadian flourishes that fit into neither tradition. In all honesty, the exact “rules” of Canadian English tend to be fairly unclear and are often disputed. Publishers churn out “Canadian dictionaries” and the government of Canada produces an official guide to the “Canadian style,” but it’s still common to hear Canadians — even very educated ones — argue about the correct “Canadian way” to spell or pronounce this or that word. Many Canadian editors and teachers simply pass down whatever rules they remember learning.

Since Canada is so deeply intertwined with American culture, most interest in Canadian English tends to centre around the ways American and Canadian English conventions deviate. Most notably, Canadian English favours the British “ou” instead of “o” in certain words with a long “uhr” sound, such as colour and favourite, and uses “re” to end certain words with a short “uhr” sound, such as centre and theatre. Only a few English words have an “official” Canadian pronunciation that deviates from standard American practice, such as “luf-tenant” for lieutenant and “shed-uale” for schedule, but these rules are not widely obeyed in practice.

Other cliches associated with Canadian English, such as speaking very slowly, ending every sentence with “eh?,” or pronouncing words like “about” and “house” as “aboot” and “hoose” (the so-called Canadian Raising phenomenon) have long ceased to be common in anywhere but the most rural and isolated parts of the country, and are now actually considered somewhat offensive stereotypes.

Canadian French

The fact that Canada has not had substantial amounts of French immigration since the 18th century is reflected in the unique form of French that is spoken by the seven million Canadians who learned it as their first language.

While it’s obviously difficult to get into too much detail about a foreign language when writing in English, the main differences between Canadian French and what is usually called “Parisian French” tend to centre around French-Canadians’ continual use of certain old-fashioned terms, pronunciations and grammar conventions that have been abandoned in modern France (what linguists call archaisms), as well as le joual, a collection of unique and sometimes vulgar or nonsensical slang terms that have been popularized by the Quebecois working-class. For political reasons, French-Canadians are also a bit more militant about avoiding the use of English terms when referring to new or modern things; for instance, in France they say l’email while in Quebec they say le courriel, a more literal translation of “electronic mail.”

- Le guide du rédacteur, the Government of Canada’s guide to proper French style

- Le grand dictionnaire terminologique, the Government of Quebec’s directory of proper French terms and usage

- OffQc, a guide to Québécois French

Most French-Canadians live in Quebec, and are the descendants of settlers from eastern France. However, there is a substantial minority of French-Canadians in Atlantic Canada as well, known as Acadians, who are the descendants of a different pattern of migration, mostly from western France. French speakers will notice a difference between the Acadian and so-called Franco-Canadian dialect, as well as the more Parisian dialect of English-Canadians who speak French as a second language. To an English-speaking ear, Canadian French often sounds a bit rougher or more guttural than European French, a fact popularized by the common stereotype that French-Canadians tend to use a lot of hard “de” sounds in their speech, while Parisians use smooth “zees.”

"W'at 's use mak' foolish on de farm? dere 's no good chances lef'

An' all de tam you be poor man—you know dat 's true you'se'f;

We never get no fun at all—don't never go on spree

Onless we pass on 'noder place, an' mak' it some monee."

Excerpt of “How Bateese Came Home” by William Henry Drummond (1854-1907), whose poems mocked the French-Canadian accent.

Official Bilingualism in Canada

Until the 1950s, it was generally taken for granted that Canada was an English-speaking country where it was proper for English to be the dominant language of business, government and culture. Under this system, English-speaking, or Anglophone Canadians generally held all important positions of power, wealth, and influence, while Quebec’s French-speaking majority remained comparatively poor and excluded. This state of affairs began to quickly change in the aftermath of Quebec’s so-called Quiet Revolution of the 1960s, when more and more Quebecers entered the middle class and began to demand their province and language be given equal status and respect. Sympathetic to their plight, the government of Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau (1919-2000) passed the Official Languages Act in 1969, which, for the first time, declared Canada an officially bilingual nation where French and English “have equality of status and equal rights and privileges.” These values were later added to the revised Canadian Constitution of 1982 as well.

In practice, official bilingualism means Canadians have the right to interact with any institution of the federal government, from an employee at their local post office to a judge of the Supreme Court, in either French or English. The 1969 Languages Act thus heralded the beginning of a new era in Canada where it suddenly became very important for all Canadians with important jobs to speak French, or at least always have a team of professional translators on hand. Today, any person who works in Canadian government, law, or military will find it difficult to get promoted above a certain rank unless they possess strong skills in both English and French, and Canadians from the province of Quebec, where bilingualism is most common, or other small corners of the country where French and English are equally spoken, are generally overrepresented in senior positions.

Official bilingualism’s other main goal was to “[foster] the full recognition and use of both English and French in Canadian society,” or, in other words, promote the speaking of French in English regions of Canada, and vice versa, in order to achieve a more seamlessly bilingual country. The Canadian government subsidizes the teaching of French in schools across Canada, as well as English in Quebec, though results have been meager. Since so few Canadians outside of Quebec have much use for French in their day-to-day lives, the language has not proved interesting to anyone beyond a small minority who seek government jobs. The Quebec government, meanwhile, has repeatedly passed laws limiting the use of English on signs, workplaces, and classrooms in order to consolidate Quebec’s identity as a purely “French society.” Today, only about 17 per cent of Canadians are said to be able to speak both French and English, a rate which has stayed pretty steady since 1969. The amount of power held by this minority continues to be a source of controversy in Canadian politics — and workplaces.

Bilingual pizza boxes.

Other Languages in Canada

Canadians who speak neither English nor French as their first language are sometimes called Allophones, and the majority of these people are either immigrants or their children. According to the most recent Canadian census, around three million Canadians speak a non-official language “most often at home,” with the most popular Allophone languages being Chinese, Punjabi, and Spanish.

Legally, one must be fluent in either French or English in order to become a citizen of Canada, but there are exceptions for the very young and very old, and in practice, it is not uncommon for immigrant Canadians in big cities to possess limited skill in anything but their birth language. This, in turn, represents one of the central dilemmas of Canadian multiculturalism: is it reasonable for places like banks, hospitals, and restaurants to accommodate immigrants by offering services in their native languages? Or is it better for national unity to insist immigrants learn the language of the majority — even if that makes life hard for those who don’t?

The question is a controversial one, and in most Canadian cities both approaches are pursued to varying degrees. A government website may feature a button for a Punjabi translation and a shop in Chinatown may have Chinese-speaking cashiers, but it may be very hard to find truly critical information, such as tax forms or legal filings, written in anything other than English or French.

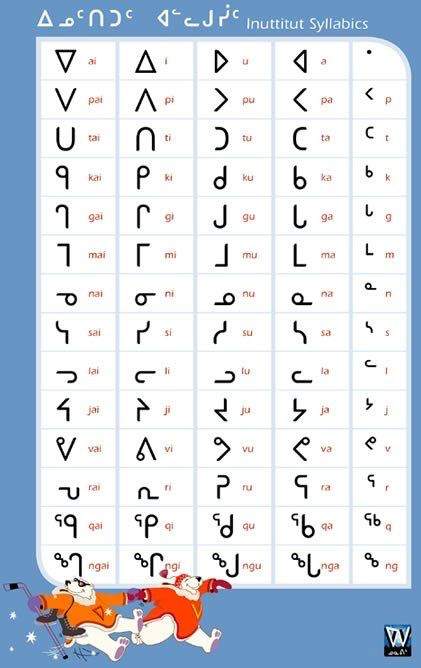

Aboriginal Languages

The aboriginal languages of Canada — much like the aboriginal people themselves — were almost entirely wiped out by European settlers. The Indian residential schools program in particular, which ran Native education in parts of rural Canada until the 1960s, had an explicit, and largely successful goal of trying to get several generations of Indigenous peoples to stop speaking their native languages as part of a larger assimilation agenda. In recent decades, attitudes have changed dramatically, however, and the government of Canada now actively tries to promote the growth and survival of aboriginal languages that sit on the brink of death.

Just over 120,000 Canadians — or about 0.4 per cent of the population — claim to speak an aboriginal language at home, with the vast majority of these being Cree-speakers in Quebec, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan, and Inuktitut-speakers in northern Canada. The northern territory of Nunavut recognizes Inuktitut as an official language alongside French and English, and the Northwest Territories gives 11 aboriginal languages official status.