No

Canadian Urban Legends

Like citizens of any country, Canadians like to share and circulate weird, wacky, or just plain interesting stories about their nation, culture, politics, and people. Some of them seem too wild to be true, and many are. Here’s a rundown of some of Canada’s most common urban myths.

Money

Is the loon on the Canadian one-dollar coin only there because the original design got lost?

Yes. According to the Royal Canadian Mint:

Initially, the Loonie as we know it was never meant to be. The original master dies of the one-dollar coin, which depicted the motif of a voyageur, were lost in transit on their way to Winnipeg in November, 1986. To preserve the integrity of the Canadian coinage system, the Government of Canada authorized a new design of the coin, which was of the loon.

Do Canada’s new plastic bills contain a special agent that makes them smell like maple syrup?

No. Though a lot of people seem to believe this, a 2013 Canadian Press story quoted an “official” from the Bank of Canada saying “no scent has been added to any of the new bank notes.”

Did the old (1986-2001) Canadian bills depict a U.S. flag flying over parliament as prelude to some horrible New World Order annexation of Canada?

No. The flag depicted on the old money was the Red Ensign, Canada’s flag between 1922 and 1965. When shrunk down and turned monochromatic, it kind of looks like the American stars-and-stripes, since both flags feature a square in the top left corner.

Snopes has written a long debunking of this myth.

Is it against the law to cut a coin in half in Canada?

Yes. According to Section 11(2) of the Currency Act, anyone who shall “melt down, break up or use otherwise than as currency” any Canadian coin is “liable on summary conviction to a fine not exceeding two hundred and fifty dollars or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding twelve months.”

Symbols

Do the points on the maple leaf on Canada’s flag represent Canada’s ten provinces?

No. Officially speaking, nothing on Canada’s flag represents anything.

The 1965 Proclamation of the national flag of Canada decrees only that Canada shall have “a red flag of the proportions two by length and one by width, containing in its centre a white square the width of the flag, bearing a single red maple leaf,” and does not designate any official symbolism. In any case, depending on how you count, the maple leaf on the flag has either nine points or 11, neither of which has any obvious Canadian symbolism given that the country has 10 provinces and (at the time the flag was made) two territories.

A 2015 statement from the federal government on the 50th anniversary of the Canadian flag affirmed “there is no special significance to the eleven points.”

Is it illegal to pick trillium flowers in Ontario?

No. The White Trillium (Trillium grandiflorum) is the official provincial flower of Ontario, which has led to a common assumption that the flower enjoys special legal protections as a result. In reality, giving official symbol status to a specific species of plant (or a species of bird or animal) is simply a ceremonial designation, with no relevance to law. As the website of the Legislative Assembly of Ontario puts it, “Contrary to popular belief, it is not illegal to pick a white trillium in Ontario.”

Variations on this myth are popular across North America, and there are similar urban legends in other provinces and American states that it’s illegal to pick the provincial/state flower. The trillium myth is probably common in Canada simply because it’s the well-known provincial flower of Canada’s largest province.

It should be noted, however, that disturbing certain kinds of plants can be a crime in some areas if the plant in question is endangered. In some rare cases, there may be overlap between an official plant and an endangered one (for example, the Minnesota Ladyslipper) which is probably how the myth began.

Sports

Is Canada’s official national sport actually lacrosse, not hockey?

Actually, it’s both. According to the National Sports of Canada Act (1994), Canada has two official sports. Hockey is the “national winter sport of Canada” while lacrosse is the “national summer sport of Canada.”

Does the “H” in the Montreal Canadiens logo stand for “les habitants,” a nod to Quebec’s rural history?

No. This myth is heavily bound up in the fact that “the habs” or “les habs” has long been a popular nickname for the Quebec hockey team.

According to the Montreal Canadiens website, the “H” in their logo simply stands for “hockey” and was added in 1916 after the team was purchased by an outfit called the Canadien Hockey Club. Prior to 1916, the team was owned by the Canadien Athletic Club and the logo featured a big letter “A” instead.

No one really knows where the “habs” nickname comes from, other than it’s an allusion to les habitants, a term for early French-Canadian agricultural settlers. It’s unclear if the habs nickname came before or after the myth about the “H” in the logo.

Is the name of the “Toronto Maple Leafs” a hilarious typo?

It’s unclear. Why is the hockey team called the “leafs” and not the more grammatically correct “leaves?” No one really knows.

There is a common myth among Toronto fans that their team was named after something called the “Maple Leaf Regiment” that fought during World War I (1914-1918), and that it’s not grammatically incorrect to pluralize a team named after a proper noun. The only problem? No such regiment existed.

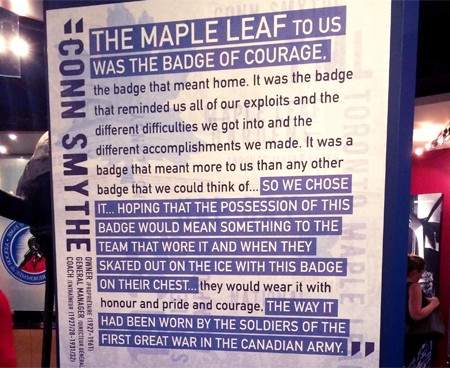

According to the Maple Leafs’ official website, it’s “not known” why the team is called what it is, though they quote team founder Conn Smythe (1895-1980) saying he was inspired by the maple leaf badges many Canadians wore during the First World War. This still doesn’t explain why he chose to pluralize the name in the way he did. Complicating matters further, there existed sports teams in Canada called “the Maple Leafs” before Smythe’s hockey team, and indeed, before World War I.

Did a Canadian invent penicillin?

No, though this is widely believed in Canada, for some reason. The discovery of the antibiotic penicillin is usually credited to a Brit, Alexander Fleming (1881-1955), a man with no evident ties to Canada. The 1945 Nobel Prize in Medicine, which was given to honour “the discovery of penicillin” went to Fleming along with Australian Howard Walter Florey (1898-1968) and German-born British immigrant Ernst Boris Chain (1906-1979), neither of whom had any Canadian ties, either.

It is likely the myth that a Canadian had something to do with the invention of penicillin just arises from people getting penicillin confused with insulin, given insulin was discovered by a Canadian, Frederick Banting (1891-1941), who won the Nobel Prize in 1923. Fleming and Banting have vaguely similar biographies.

Monarchy

Does the British monarch own all the land in Canada?

No, not all, and no, not personally.

According to the Canadian Encyclopedia, around 90 per cent of all land in Canada is owned by either the federal or provincial governments (in a very rough 50-50 split) while the remaining 10 per cent is privately owned.

Because Canada is a monarchy, Canadian law refers to the legal authority of the Canadian government as “the Crown,” and one often hears government-owned land described as “Crown land” or land “owned by the Crown” as a result. Because Canada is a constitutional monarchy, however, the powers of the Crown are exercised by politicians and bureaucrats on behalf of the current king or queen, with the actual monarch no longer having any independent, decision-making authority.

Though King Charles III (b. 1948), in his capacity as Canada’s monarch and head of state, may technically hold symbolic legal authority over the vast majority of Canadian land, he as an individual holds no power under Canadian law to unilaterally buy, sell, lease, or trade “his” land, nor does he personally secure any royalties or rent from any activities that occur on any of it.

For more on the “Crown,” see the question about Native rights below.

On old Canadian stamps and money, was there a subliminal image of the devil in the Queen’s hair?

Yes, though it was obviously an accident.

In 1954, following Elizabeth II’s (1926-2022) coronation, the Bank of Canada produced a new series of Canadian banknotes featuring a portrait of the country’s new queen. If you looked at the Queen’s hair in these portraits closely enough, it was possible to make out a vague, yet grotesque-looking face in her curls. This was a complete coincidence, however, as the banknote portrait was based on a 1951 photograph, which featured the same face-shaped curls, caused by the lighting in the shot. Nevertheless, by 1956 the controversy was enough that the Bank of Canada edited the Queen’s portrait to eliminate the creepy curls, making so-called “Devil’s Face” bills now much sought by collectors.

Canadian Coin and Currency has a full summary of the controversy.

Is the Hudson’s Bay Company still legally obligated to give the British monarch a package of beaver pelts (or some such archaic, colonial-era offering) every time they visit Canada?

This used to be true, but isn’t anymore.

According to the HBC website, the Bay’s 1670 Royal Charter originally included a stipulation calling for a “payment of a rent of ‘two elk and two black beaver’ whenever the Sovereign or his Successors should enter into the area of the Company’s tenure,” and the company fulfilled this obligation — known as the Rent Ceremony — the first four times British royalty visited Canada. In 1927, 1939, and 1959 they gave the obligatory elk and beaver pelts to Prince Edward of Wales (1894-1972), King George VI (1895-1952) and Queen Elizabeth II, respectively, and in 1970 the company organized a bit of a PR stunt by donating two living elk and beavers to Winnipeg’s Assiniboine Park Zoo in the Queen’s name. The year 1970 also saw the HBC charter get amended and modernized, and among other things, the royal fur payment tradition was removed.

Aboriginals

Did Canada, England, or the Hudson’s Bay Company purposely try to kill Indians by giving them blankets (possibly even iconic HBC “stripe” blankets) infected with smallpox?

No. On their website, the Hudson’s Bay Company calls this “one of the most widely propagated and misunderstood stories in North American history.” They track the legend to some letters exchanged by British colonial officials in the 18th century, in which a similar idea was discussed, but “there is no hard evidence that this plan was ever enacted.” The scientific concept that diseases can be spread by germs or infected materials was not mainstream knowledge until the mid-19th century.

Do Canada’s aboriginal nations only have a legal relationship with the British monarch, not Canada?

No. This misconception is widely held by many aboriginal leaders and continues to cause problems for First Nations-Canadian relations, most recently during the Theresa Spence hunger strike of 2012.

Though most of Canada’s aboriginal bands signed treaties made in the name of the king or queen of the United Kingdom, these various kings or queens were not personally involved in creating said treaties. In a constitutional monarchy, politicians and bureaucrats merely perform actions on behalf of the monarch, since the monarch is technically the source of all political power. In practice, these treaties were negotiated, written, and drafted by either British or Canadian bureaucrats and politicians.

When Canadians speak of “the Crown” they are referring to the abstract authority of the entire Canadian constitutional monarchy political system, and not literally a person wearing a crown. Responsibility for honouring and enforcing aboriginal treaties in Canada is explicitly the jurisdiction of the government of Canada, as indicated in Section 91(24) of the Canadian Constitution Act, 1867 and Sections 25 and 35 of the Canadian Constitution Act, 1982.

...it is hereby declared that (notwithstanding anything in this Act) the exclusive Legislative Authority of the Parliament of Canada extends to all Matters coming within the Classes of Subjects next hereinafter enumerated;... 24. Indians, and Lands reserved for the Indians.

From Section 91 of the Canadian Constitution Act, 1867.

Was South Africa’s racist apartheid system based on Canadian aboriginal policies?

No. According to a 2007 academic paper published in the Journal of South African Political Studies (Terminologies of Control: Tracing the Canadian-South African Connection In a Word), there exists “little evidence, beyond ‘scraps’” that the South African government was ever inspired by Canadian policies. The author concludes that the story “appears to be a myth” that is “employed powerfully for political ends.”

Government, Politics, and History

Are members of parliament legally required to present every petition they receive — no matter how wacky — to the floor of the House of Commons?

No. Though this belief has been cited in defense of MPs who have read some rather strange petitions, most recently Green Party MP Elizabeth May’s (b. 1954) reading of a 9/11 “Truther” petition in the winter of 2014, the Parliament of Canada website states that “members are not bound to present petitions and cannot be compelled to do so,” though some might consider it a moral obligation.

It should also be noted that there is no “magic number” of signatures required for a MP to bring a petition to Parliament’s attention, either.

Are the Turks and Caicos islands in the Caribbean going to become Canada’s 11th province, or did they “almost” join Canada at one point?

No. Though the idea has been discussed over the decades, it’s currently nowhere close to happening, nor was it ever close to happening in the past.

During Canada’s mid-19th/early 20th century period of geographic expansion, it was common for Canadian politicians to argue all British colonial possessions in America, which is to say the many islands of the British West Indies, and the Latin/South American territories of Guyana and Belize (formerly known as British Honduras), should be placed under Canadian control — partially for economic reasons, partially to help Britain “protect” them from American domination, partially for patriotic reasons of glory and empire-building. Prime Minister Robert Borden (1854-1937, served 1911-1920) was particularly fond of this idea, and there are numerous cables between him and London in which the Canadian PM attempts to make the case for “bringing these lands into Confederation.” Britain’s colonial office was politely tolerant of the proposal, but talks remained theoretical, and petered out after Borden left office.

The romantic notion of a Canadian Caribbean did not die, however, and as the decades progressed, and most of the region’s islands became independent countries, the Turks and Caicos Islands eventually emerged as the focus of Canadian attention, remaining, as they do, the largest surviving British colonial possession in the North Atlantic. Though eccentric Canadian politicians continue to raise the idea of absorbing the islands now and then — most recently backbench Conservative MP Peter Goldring (b. 1944) and before that Nova Scotia legislator William Langille (b. 1944), who in 2004 successfully convinced the Nova Scotia legislature to pass a motion of support — Canada’s foreign minister has declared Ottawa “is not in the business of annexing islands in the Caribbean,” and the prime minister of Turks and Caicos has “firmly and publicly disparaged the prospect” according to a 2013 article in the National Post. In his 2015 book, Canada: A New Tax Haven: How the Country That Shaped Caribbean Tax Havens is Becoming One Itself, author Alain Deneault suggests contemporary interest in this idea is largely being driven by rich Canadians who want to see a new province with lax, Caribbean-style tax laws.

For more information, see Northern Shadows: Canadians and Central America (1989) by Peter McFarlane.

Did future prime minister Pierre Trudeau protest World War II by riding around Montreal on his motorcycle while wearing a Nazi helmet?

It’s unclear.

According to biographers Max Nemni and Monique Nemni, authors of Young Trudeau: 1919-1944: Son of Quebec, Father of Canada, the motorcycle/helmet story “has as many variants as there are storytellers, each embroidering freely on the known facts.” Credible sources do seem to agree, however, that young Pierre and his friend Roger Rolland (1921-2011) played a prank in 1942 that involved dressing up in European military uniforms and riding around on their motorbikes.

The Nemnis quote Rolland’s memory of the prank, in which he recounts that it was he, not Trudeau who wore the German army helmet (from the First World War, incidentally). Rolland similarly claims, in the Nemnis’ words, that the point of the prank was simply to surprise some friends with “outlandish disguises,” — “not to convey some political message.” The Nemnis themselves seem skeptical, and question “how two educated young men in their early twenties, in the midst of a world war, could find such a prank appropriate.”

Did prime minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau draw the Doonesbury comic strip, or is he at least related to the guy who did?

Doonesbury has always been drawn by the American cartoonist Gary Trudeau (b. 1948). He is of French-Canadian heritage, and as such is very distantly related to Pierre Trudeau through their common ancestor Etienne Trudeau (1641-1712). According to the book Ghost Empire: How the French Almost Conquered North America “virtually every person named Trudeau in North America” is a descendant of Etienne Trudeau.

Gary and Pierre did not know each other.

Did the lyrics to the theme song of Tiny Toon Adventures make reference to Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney?

No. Only a popular parody version. The actual lyrics of the nineties-era animated series go:

We’re tiny, we’re toony/we’re all a little loony/and in this cartoony/we’re invading your TV!

The parody version, spread by Canadian kids on the playground, but never actually heard on the show itself, went:

We’re tiny, we’re toony/we can’t afford a loonie/’cause Brian Mulroney/invented GST!

Did Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau once compare US-Canadian relations to a “mouse sleeping with an elephant?”

Not in those exact words, no. In a famous 1969 speech to the Washington Press Club, Prime Minister Trudeau said this:

Some of our policies may be of interest to this audience, and with your permission I should like to speak about several of them in a few minutes. But first let me say it should not be surprising if these policies, in many instances, either reflect or take into account, proximity of the United States. Living next to you is in some ways like sleeping with an elephant. No matter how friendly or even-tempered is the beast — if I can call it that — one is affected by every twitch and grunt.

Pierre Elliott Trudeau, 1969

Note that Trudeau’s analogy was simply about “sleeping with an elephant” in general; at no point did the prime minister use a mouse metaphor for Canada. Nevertheless, the notion that Canada is a mouse to America’s elephant quickly became mainstream, and associated with this speech.

Trudeau’s son, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, has often said he wants Canada to be thought of as a “moose” not a “mouse,” a clarification that makes no sense unless one is familiar with the popular misquotation of his father.

For example, consider this 2018 exchange with NBC’s Chuck Todd (b. 1972):

TODD: Your father said this in 1969: “Living next to you” — referring to the United States — “is in some ways like sleeping with an elephant. No matter how friendly or even-tempered is the beast, one is affected by every twitch and grunt.” Do you sleep worse these days? Do you sleep unsettled?

TRUDEAU: You know, I’ve taken a different take on that than my father. I think we’re more of a moose. We’re still —

TODD: (interrupting, confused) You’re the moose?

Did Prime Minister Kim Campbell once make the bizarre claim that “an election is no time to discuss serious issues”?

Not really. This is one of the most famous Canadian political quotations of all time, but according to the memoirs of Kim Campbell (b. 1947), Time and Chance (1996), it’s cited completely out of context.

During the 1993 federal election, Kim Campbell’s Conservative government was accused by the NDP of having a “secret agenda” to unilaterally reform various social programs, including unemployment insurance, without first engaging in customary consultations with the provinces. Campbell responded by reaffirming that she was absolutely committed to holding such discussions — after her government was re-elected.

“I was then asked [by a reporter],” writes Campbell, “if I didn’t think that it was possible to have that dialogue during the election campaign, and I replied ‘I think that’s the worst possible time to have that kind of dialogue.’”

“When [the reporter] asked why, I explained, ‘Because it takes longer than forty-seven days to tackle an issue that’s that serious.’”

She later added, “This is not the time, I don’t think, to get involved in a debate on very serious issues.”

In other words, Campbell’s comment about not wanting to discuss “serious issues” during an election was quite focused and specific. She did not want, as prime minister, to discuss social program reform with the provincial governments during the election she was currently running in, though out of context her phrasing made it sound like she was making a broader statement about serious issues and elections in general.

Did Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper once ominously promise that “you won’t recognize Canada when I get through with it?”

No, this is a largely fictitious quotation that seems to have been invented by Harper’s partisan enemies by taking a quote out of context and then proceeding to twist its meaning even further.

In 2004, following his election as leader of the Conservative Party of Canada, Stephen Harper (b. 1959) gave a speech in which he bragged that his party would “create a country built on solid Conservative values not on expensive Liberal promises. A country the Liberals would not even recognize. The kind of country I want to lead.”

A few months later, during the 2004 federal election campaign, the Liberal Party ran an attack ad against Harper, stating, in part that “Stephen Harper says when he’s through with Canada we won’t recognize it. You know what? He’s right.”

It’s from merging these two very different statements together that we wind up with the “when I get through with it” misquote.