No

Religion in Canada

Life in Canada isn’t just about the material world. Since the country’s earliest days, many Canadians have relied on organized religion to provide their lives with a deeper sense of spiritual purpose.

Canadian Attitudes Towards Religion

Canadians are a measurably religious people. According to a 2022 Angus Reid poll, over 75% of Canadians claim to be members of some sort of religious tradition, with solid majorities also stating they believe in fundamental religious concepts like the existence of God, prayer, divine intervention, and heaven. Though most Canadians are Christians, rising immigration from countries outside Europe has seen Canada grow far more religiously diverse in recent decades, with increasing numbers of Canadians claiming adherence to traditionally Asian and Middle Eastern faiths.

That said, while many Canadians may be personally religious, most also respect the principle of secularism, or keeping one’s faith a mostly personal, private matter. Because Canadians have so many distinct (and often conflicting) thoughts about God and religious morality, learning to respect the faith of others while still honouring your own has long been a vital part of maintaining a peaceful, cooperative country.

Christianity in Canada

Since the vast majority of settlers and immigrants who colonized Canada came from Europe, European-style Christianity has long been Canada’s most popular religion, and today over 23 million Canadians, or more than 66 per cent of the population, claim Christianity as their faith. Millions of other Canadians may not be practicing or believing Christians, but will still identify themselves as being of Christian heritage. Even in an increasingly secular age, much of Canadian culture accordingly retains strong Christian influences, from what holidays are celebrated, to how traditions like weddings and funerals are conducted, to the philosophical roots of the Canadian criminal code.

Christianity is based on the teachings of the martyr Jesus Christ (c.6 BC – c.30 AD), who Christians believe lived as the divine son of God during his life, and forms one-third of God’s holy trinity that must be worshiped to achieve salvation. The Christian Bible consists of two volumes, the Old Testament and New Testaments, with the latter spelling out Christ’s rules for righteous living.

Despite their shared love of Jesus, Canadian Christians have always been strongly divided about how to practice their faith, and three self-proclaimed Canadian Christians may attend three different churches and believe three rather distinct and conflicting interpretations of the Bible and Christ’s instructions. What follows is a brief overview of some of the major branches of Christianity present in Canada.

Catholics

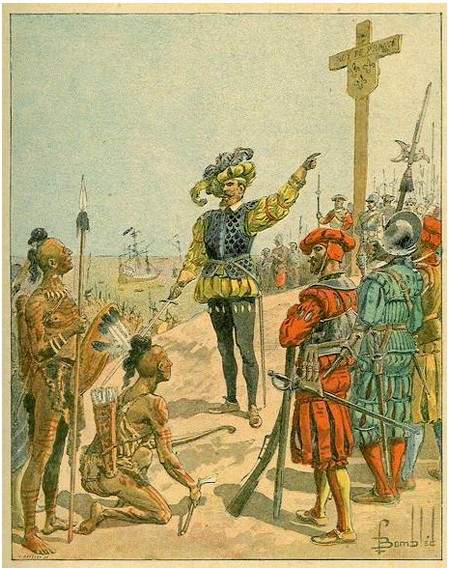

Roman Catholicism was the faith of Canada’s original European settlers, and to this day remains the largest denomination of self-identified Canadian Christians. Originally brought to the eastern coast of North America by French colonists in the 16th century, Catholicism spread quickly across Canada thanks to the aggressive efforts of French missionaries, particularly members of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits), whose journeys across the harsh terrain of the vast Canadian landscape have long been the subject of religious and secular legend. Numbering around 12 million people, today Catholics comprise just over 50 per cent of Canadian Christians.

Headquartered in Rome, Italy the Roman Catholic Church believes its legitimacy as the one true Christian church flows from its leader, Pope Francis (b. 1936), who is said to be the modern-day successor of the many successors of St. Peter (c. 1st Century, AD), who was in turn the handpicked successor of Jesus Christ himself. Catholicism is the most rigidly hierarchical form of Christianity, with the objectively “correct” interpretations of biblical teachings flowing to parishioners downward, through the Pope and the clergymen he appoints, known as cardinals, bishops and priests. In modern times, the church has become particularly known for its strongly conservative views on sexual and reproductive issues, including birth control and abortion.

For centuries, Catholicism in Canada was particularly associated with French-Canadians and the province of Quebec, whose clergy were strong proponents of the most hardline, or ultramontane faction of the church well into the 20th century. Fear and suspicion about this fundamentalism led to a lot of anti-Catholic bigotry among non-believers for much of Canadian history, and until quite recently it was very unusual for Canadian Catholics to marry non-Catholics or for Catholic children to attend non-Catholic schools. Today, Catholicism has declined remarkably among Quebeckers, but remains strong among other communities in Canada who trace their roots to traditionally Catholic countries such as Italy, Ireland, Portugal, Poland, the nations of Latin America and the Philippines. The Canadian constitution still guarantees a right to state-funded Catholic schools in some provinces.

Protestantism in Canada

Protestantism is simply a catch-all name for any faction of Christianity that is not Catholic. Though about 24 per cent of Canadians consider themselves Protestants, the sheer number of Protestant churches in the country makes it a very hard identity to generalize. Its major branches are:

Anglicanism

Historically, the Anglican Church of Canada was Canada’s leading Protestant alternative to Catholicism, and the preferred church of the country’s early English colonists and missionaries in the same way the Catholic Church was favoured by the French. In the 18th and 19th centuries especially, Anglicanism was the church of Canada’s powerful British-born elite, and closely associated with conservative-minded men who dominated the country’s politics and commerce. Today, however, it has declined to third-place status in the Christian rankings, with about 2.5 million followers (or around seven per cent of the population).

Formally, the Anglican Church of Canada is a descendant of the British Church of England, which was established in the 16th century as a breakaway faction of Roman Catholicism. It was the official religion of the British Empire, and was spread by missionaries to most British colonies during the age of imperialism. Though still formally headed by the British Monarch (who is still given the official title “Defender of the Faith” in Canada), Anglican churches now exist as fully independent entities in dozens of sovereign nations. Leadership of the Anglican Church of Canada is held by a council of bishops who hold final say over major theological questions, though individual church congregations have a lot of self-governing power.

In recent years, Canada’s Anglican church has become particularly well-known for its controversially liberal positions on certain matters of Christian dogma. In 1975 it approved the ordination of female priests, which was followed by the approval of female bishops in 1986. In 2016, after decades of divisive debate, the church formally endorsed same-sex marriage.

St. Paul's Anglican Church in Trinity, Newfoundland.

meunierd/Shutterstock

During the 17th and 18th centuries, the British Isles went through a phase of so-called “evangelical Protestantism” that saw many new, democratic-populist churches arise in opposition to the then-authoritarian dominance of the Church of England. All would eventually find their way to North America.

The United Church of Canada

Presbyterianism was a largely Scottish Protestant tradition that eschewed a national hierarchy of bishops in favour of a network of independently-run churches with priests chosen by a local council of elders, known as presbyteries. Those known as Congregationalists went even further, and argued only the church congregation itself could appoint priests. Methodists, meanwhile, eschewed priests altogether and promoted the idea that each individual Christian held an obligation to preach and promote his faith, particularly to the poor and downtrodden.

These three traditions earned a share of followers in Canada, and during the 19th and 20th centuries enjoyed growing support among middle class Canadians whose background was neither French or English, particularly Scots, Germans, Russians and Scandinavians. Sensing more similarities than differences, the leading representatives of the three churches voted in 1925 to merge into one United Church of Canada, which now sits as the country’s single largest Protestant denomination, with over 2.5 million followers.

Reflecting their founding desire for unity rather than division, the modern United Church of Canada remains a loose network of independently-governed churches (some of which still identify as Presbyterian, Methodist, or Congregationalist) promoting a highly individualistic interpretation of scripture and a personal relationship with God at the expense of a clear and specific code of morality decreed from church authority figures. In practice, Canada’s United Churches are usually considered to be the most theologically liberal and permissive of any major Protestant denomination, and its leaders are well-known for their activism in pushing controversially left-wing political and social causes.

Other Protestant Churches

There are over half a million Baptists in Canada, another loosely organized, non-hierarchical Protestant denomination best known for its adult baptisms and fiery, conservative sermons. Canadian Lutherans are almost as numerous, and participate in a fairly conservative and traditional Protestant church known more for its ethnic makeup (primarily German and Scandinavian immigrants) than any particularly distinctive modern traditions.

The dozens of other small Protestant sects whose followers have left some cultural impact on Canada include the charity-focused Salvation Army, the strict and puritanical Jehovah’s Witnesses, and three churches based around 19th century prophets: the Seventh-Day Adventists who follow the teachings of Ellen White (1827-1915), the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (the “Mormon” church), whose faith is built around the revelations of Joseph Smith (1805-1844), and the Church of Christ, Scientist (the “Christian Scientists“) which was founded by Mary Baker Eddy (1821-1910). The Canadian Prairies are home to a significant population of followers of various rural, isolationist, fundamentalist Christian sects from 17th century eastern Europe as well, including Mennonites, Hutterites, and Amish, who emphasize a commitment to self-sufficiency and simple living.

These days, more and more Canadian Christians are opting out of denominational Protestantism altogether, in favour of simpler, non-hiearchical, non-sectarian evangelical churches that preach a mostly literal interpretation of the Bible and promote a highly personal relationship with God. The term “evangelical” itself refers to the practice of aggressively seeking to spread awareness of the faith to non-believers, partially via so-called “born-again” adult conversions. Modern, image-conscious and known for its large, inclusive “mega-churches,” evangelical Christianity is Canada’s fastest-growing form of Protestantism and has made considerable inroads among youth, immigrants and suburbanites. At the same time, it’s also earned a great deal of controversy due to its active support for conservative political causes, particularly opposition to homosexuality, trans rights and abortion.

Christian hip-hop star TobyMac performs at WonderJam, Canada's largest Christian rock concert.

Sean Stephens/Flickr

Christian culture in Canada today

Historically, Canadians were generally seen as being a fairly conservative people, with the strong Christian faith of many Canadians playing a large role in this culture. Going to church every week was once very common, many children learned about the Bible or recited Christian prayers in school, and statements about the importance of upholding Christian beliefs or doctrines were common in politics. Many once-common Canadian attitudes and opinions, such as the belief that women should not work but instead stay home and tend to the house and children, that couples should not live together before getting married, or that homosexuality is offensive, were usually rooted in a desire to uphold Christian teachings. It is not uncommon for many Canadians over 40 to have some familiarity with these sorts of attitudes and many grew up believing them.

In more recent decades, however, there has been a strong push towards secularism in Canadian society, in which Christianity is no longer see as “Canada’s religion,” but rather one of many religions in Canada’s multicultural society (as this chapter documents!), and not one that should be given any special status as a result. Arguments that assume Christianity is the one true religion have become far less common, and many Christian traditions like public prayers or even saying “Merry Christmas” in December have become more controversial or taboo, as they become seen as efforts to “impose” Christianity on people who might not be believers. It’s worth noting that this trend has occurred at a time when many Canadians of Christian backgrounds are themselves growing more disillusioned with a religion they may no longer believe in, or associate with the less-tolerant conservative attitudes of the past.

Today, openly identifying oneself a “Christian” in Canada can often be seen as a somewhat political statement; a declaration that you see yourself as resistant to the larger secular drift of Canadian culture. Strongly traditionalist or conservative Christians are often called “social conservatives,” and are usually associated with the Catholic or Evangelical churches, as opposed to the more progressive Protestant ones. Big cities in Canada tend to be the most secular and least Christian parts of the country; rural areas tend to the most Christian and most socially conservative.

Judaism in Canada

At just under a million, Canada’s Jewish population may seem small, but it’s actually the fourth largest Jewish community on earth, eclipsed only by the Jewish populations of Israel, France and the United States.

Judaism is an incredibly ancient religion founded some three thousand years before Christ and is based around lessons contained in the Old Testament, as well as centuries of commentary by Jewish thinkers compiled in a volume known as the Talmud. At the same time, many Canadian Jews may view their faith as much as a cultural identity as a spiritual one, with equal importance placed on upholding various age-old Jewish traditions, customs and holidays that help maintain a sense of permanent community and identity. The most religiously devout Jews are known as Orthodox, while more secular ones are known as Reform.

Most Canadian Jews were born in Canada but are descended from Eastern European immigrants who came to Canada after World War II (1939-1945); prior to that, Canada maintained an infamously anti-Semitic immigration policy, prompting most North American Jewish refugees to settle in the United States instead. Today, Canada’s largest Jewish communities are located in the urban centres of Toronto and Montreal, where their presence has made a significant influence on local art, politics, commerce and cuisine.

Islam in Canada

Islam is considered to be the world’s third major monotheistic (single-god) faith, and like Judaism and Christianity, it traces its origins to the ancient Middle East. Its key tenets include reverence for Mohammad (c. 570 – c. 632), a man believed to be God’s final prophet on earth, and the Koran, a holy book transcribed by the Prophet to document God’s instructions to the faithful.

With over a million Canadian followers — known as Muslims — Islam is said to be the fastest-growing religion in modern Canada, a fact which is entirely due to a recent influx of Muslim immigrants from Islamic nations. Of these, most hail from a small group of countries in south Asia and the Middle East, namely Iran, Pakistan, India, Egypt, Syria, and Lebanon, and the practice of the faith in Canada remains heavily tied to the cultures of these communities.

Of all of Canada’s major faith groups, Muslims remain the most controversial, with polls routinely showing them to be amongst the least trusted segments of the population. This is partially due to the global rise of Islamic terrorism since September 11, 2001, which has helped taint the faith with negative associations of violence and fundamentalism, and partially because of a broader secular anxiety regarding the religion’s traditionally conservative views on women’s rights and freedom of speech. As the country’s Islamic population continues to rise, such tensions seem likely to continue, but so too are more aggressive attempts to promote interfaith understanding.

Sikhs in Surrey, British Columbia stand on the sidelines of the city's annual Vaisakhi Festival.

Michelle Lee/Flickr

Other Religions in Canada

There are about 500,000 Hindus in Canada, mostly Indian immigrants, who practice a largely unorganized but incredibly complicated, millennia-old religion based around the veneration of many different gods and ancient stories of morality and virtue. Canada’s similarly-sized Sikh population is also dominated by Indian immigrants, but its followers obey the teachings of the Guru Nanak (1469-1539) and his nine successors, who preached a message of veneration of a single god and a strict lifestyle of modest, moral living. Sikh men can be easily identified by their long beards and turbans. Like Islam, the culture of Hindus and Sikhs in Canada remain heavily tied to the immigrant communities they dominate.

Canada’s Buddhists are another immigrant-heavy group; in this case, mostly emigres from China and Japan. It’s sometimes debated whether or not Buddhism is actually a religion at all, since it does not engage with larger questions of god or salvation, but rather provides philosophical guidelines for ethical, happy living, particularly meditation and material sacrifice.

Though the majority were converted to Christianity during the colonial era, many aboriginal Canadians continue to hold certain traditional spiritual beliefs that predate European contact. Broadly based around a veneration for nature and animals, morality parables and natural sacraments, aboriginal spirituality is often combined with Christianity to create a distinctive hybrid faith.

Lastly, Canada is also home to a not-insignificant number of Pagans, Wiccans, Scientologists, Hare Krishnas, and Swedenborgian or “New Age” spiritualists, though with such comparatively small groups of followers, all have struggled mightily to gain mainstream acceptance.

Irreligious Canadians

Along with Muslims and Evangelical Christians, the fastest-growing segment of Canada’s religious population consists of those who are not religious at all. The 2022 Angus Reid survey found 25% of Canadians claiming to have “no religion” with eight per cent, or almost three million Canadians, claiming to be outright atheists — people convinced there is no god.

It can be difficult to measure the exact degree of faithlessness in Canada. Many of those who consider themselves “not religious” may still believe in God, or even the teachings of a specific faith, but simply never attend an organized church. Likewise, many Canadians who do consider themselves religious may do so primarily for cultural or identity reasons, and not actually respect or follow any of the rules of “their” supposed faith in their day-to-day lives. Millions claim the label of “agnostic” — folks who simply haven’t reached a conclusion on God or religion one way or another. Canada’s atheist and agnostic community tends to be dominated by Canadians from Christian backgrounds who have drifted away from their family’s faith over time, with immigrants less likely to identify as non-believers.

Though the avowedly irreligious may be a minority, Canada remains a nation with a strongly secular culture just the same. Most Canadians now take for granted the idea that religion is a mostly private matter, with discussions of God and spirituality reserved for church, family or other members of the faith, but rarely strangers or non-believers. Politically, there’s also a strong support for the concept of separation of church and state, or the idea that politicians should not use their powers to promote the values of one specific religion while in office, nor should religious leaders use their powers to affect the political process. In practice, of course, neither side always obeys these rules, but they nevertheless represent a certain idealized standard of conduct for both religious and secular Canadian alike in an inclusive age.